|

| Saa Sabas, Ebola survivor from southern Guinea: "I felt so tired and uncomfortable." |

The Ebola outbreak in West Africa has hit "unprecedented" proportions, according to relief workers on the ground, with the WHO reporting 844 cases including 518 deaths since the epidemic began in March.

There is no cure or vaccine to treat Ebola, but the aid agency MSF has shown it doesn't have to be a death sentence if treated early. Ebola typically kills 90% of patients but the death rate in this outbreak has dropped to roughly 60%.

One man who survived the disease describes how the virus took hold.

How did you contract Ebola?

Map: Ebola spreads in West AfricaMap: Ebola spreads in West Africa

Inside an Ebola clinic in Guinea

I am an agronomist and I have two children, one boy and one girl. I work in the pharmacy at the health center of Gueckedou in southern Guinea. When my father was hospitalized at the health center I naturally volunteered to be at his bedside so other family members would not have to make the daily trek of tens of kilometers, traversing the trails between their village and the facility. I cleaned him when he vomited and also did his laundry. I also often gave him food and drink. He had diarrhea at least eight times per day but I did not know he was suffering from Ebola.

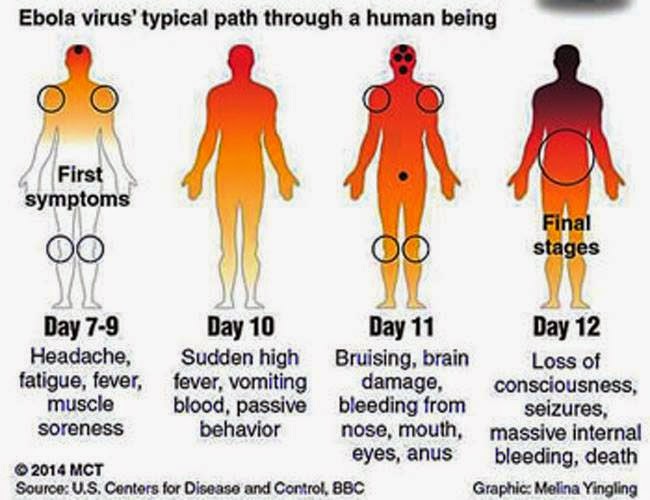

Five days after being hospitalized, [my father] passed away. After his death the medical staff realized he had presented Ebola symptoms and as I had close contact with him, it meant that I was at risk. So they told me that I needed to be followed up for 21 days and if ever I felt a small fever I had to come to the health center. The countdown then started for me: after nine days I got fever and this persisted until the 11th day. Finally I went to the treatment center -- where I did an Ebola test which was positive.

What were the symptoms? How did you feel while you were ill?

I first got a fever which persisted. My body temperature reached nearly 40C (104 degrees Fahrenheit). After that I had diarrhea, vomits, dysentery and hiccups [all symptoms of Ebola]. I went to the toilet several times a day and I felt so tired and uncomfortable.

Fighting Ebola through education

Ebola scientist: 'It's spectacular'

How and where were you treated?

I received medical assistance at the Ebola treatment center, put in place at the health centre of Gueckedou. The medical staff provided me with oral medications and infusions. They also provided me with food. I suffered at lot in the beginning with diarrhoea and hiccups but with the treatment I started to feel better.

What was the initial reaction in your home village after you recovered?

Joy, for my family because everyone thought that I would not survive this disease as many others people had died. However before the medical staff released me to go back to my family they tested me three times to make sure that I really had recovered. Afterwards they gave me a certificate of discharge. They also visited my family, the leaders and elders of my community to inform them that I had recovered and I was no longer contagious. Despite this, I was stigmatized. Some people avoided me in the beginning but now, over time, they have learned to accept me. Now they call me "anti-Ebola."

Some people avoided me in the beginning but now, over time, they have learned to accept me. Now they call me 'anti-Ebola'

Saa Sabas

You're now working with Red Cross volunteers in Guinea to raise awareness of the disease: what lessons are passing on?

I am part of a team of Red Cross volunteers, visiting communities, raising awareness on how to prevent the spread of the disease. One of the messages I try to pass on to the communities is to go early to the health center when sufferers first feel symptoms. The treatment is free of charge. People there will give you food and clothes and you can get a chance to survive.

What's your message for the outside world about Ebola? How can they help?

Everyone should be mobilized. We need to educate people and increase the sensitization. This is the key to stop the dangerous disease Ebola.

Many people have already died, that is why I participate in activities [to educate people]. I urge people to go the isolation and treatment centres if they experience the earliest symptoms of the disease, to increase their chance of being cured and surviving.